Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics: A Retrospective

And are fairy tales for children or adults? Or both?

I have loved fairy tales for as long as I can remember. It started (and quite frankly continues) with illustrated books of fairy tales. Just like how most children would pester their caregivers for the newest toys, would pester mine for the latest fairy tale books at the book store that caught my attention.

But my love of fairy tales did not pertain only to books; I was (and still am) equally enraptured on the myriad of ways fairy tales can be adapted for film and television. I was a child of the 2000’s, so I grew up on the series Simsala Grimm and The Fairytaler (shout out to those who remember these!) and the Barbie fairy tale films.

When I finally had access to the internet, the very first things I searched for was, you guessed it, fairy tale-related media. The first thing I remember finding and watching on the internet was Saban’s My Favourite Fairy Tales series (originally Sekai Dōwa Anime Zenshū). It was originally an educational series meant to teach English to Japanese children, but when it was localised into English, they completely rewrote the rather basic dialogue from the original into something more engaging for American audiences, who were then largely unaccustomed to anime or Japanese media in general. Or at least unaware that what they were watching came from another country.

There was another series I found at the time that had also been localised by Saban. It was originally called Grimm Masterpiece Theater (Gurimu meisaku gekijō) for the first season, and New Grimm Masterpiece Theater (Shin Gurimu Meisaku Gekijō) for the second, but when it was dubbed into English, it was retitled Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics. Perhaps you’ve heard of it. Perhaps you’ve even seen it when you were younger. If not, then this post should serve as an introduction to the series.

Not only is this one of my favourite fairy tale series, but one of my favourite series in general. Most of its fans are millennials who have fond memories of watching it back in the late 1980’s. I am one of the exceptions: I watched low-quality uploads of the series as a burgeoning middle-schoolers around the early 2010’s. And yet it made a profound impression on me, both as a lover of fairy tales and as a (now disgruntled) animation fan.

I recently reconnected with the series after finding and purchasing two Spanish storybooks based on episodes from the series while traveling to the Spanish city of Cádiz. These storybooks are based on the episodes “Puss in Boots” and “The Golden Goose” and they come from the direct-to-VHS series Videocuentos Infantiles (Videotales for Children). Shoutout to millennials from the Spanish-speaking world who remember that series! This made me want to rewatch the series in its entirety and, well, this is the result!

This post is less of a review of the series and more of an essay explaining its appeal, both for me and overall. If you want a proper review of the series, the one from Star Cross Anime more or less conveys my overall thoughts on the series. As to be expected, there were a few opinions in that review that I disagree with, mainly on the animation (which I think is better than just okay, and that for what it is and for its time period, it’s pretty good, even great I’d say), and the choice of episodes for the worst list. Also, because I’ll be mostly talking about the English version of the series, I’ll be referring to it by its English title.

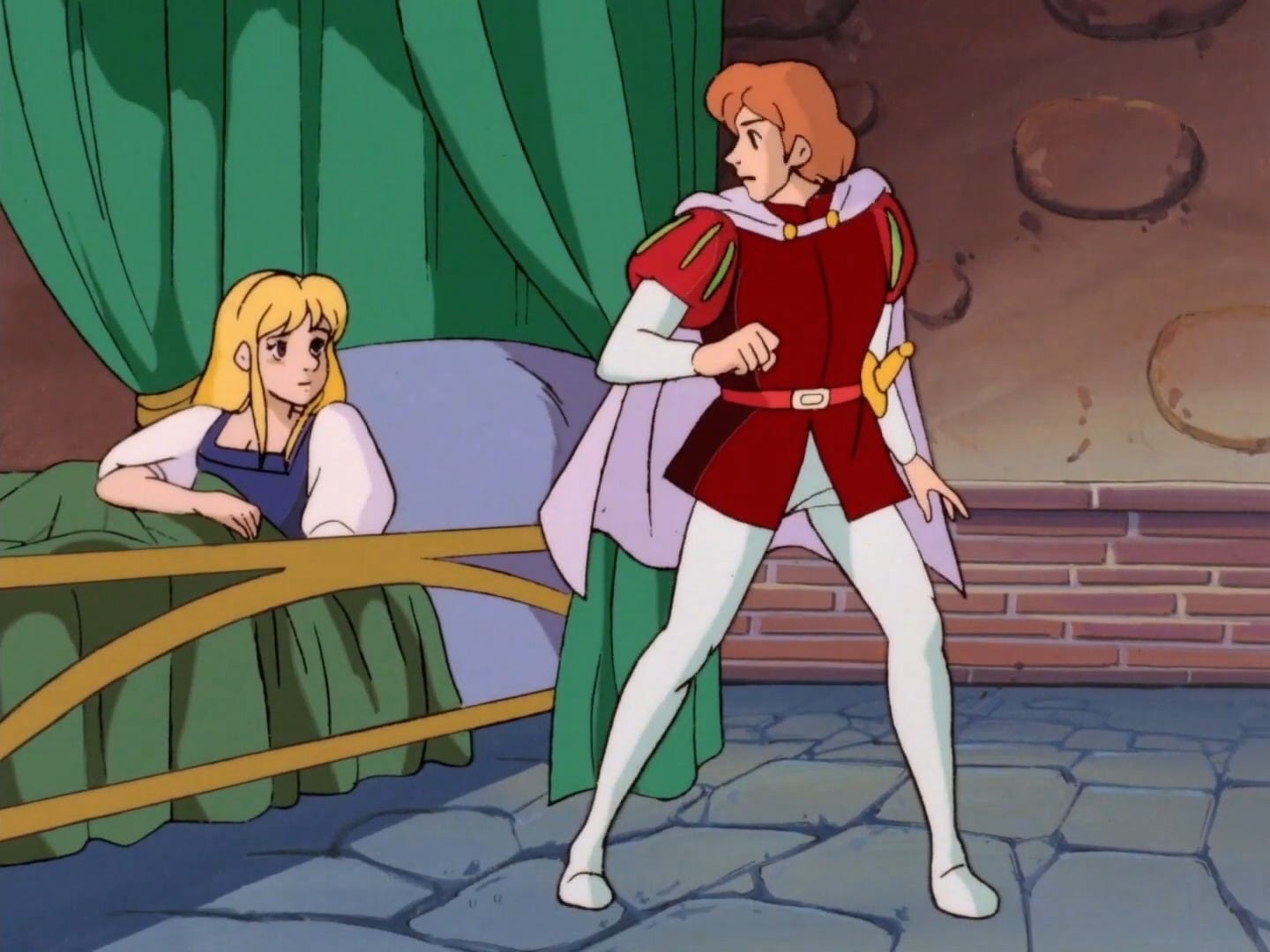

Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics is an anime anthology series produced by Nippon Animation the late 1980’s. It was part of a larger stream of anime series that adapted Western literature, presumably to introduce Japanese children to classic literature outside of their country. Each episode is a standalone retelling of one of the Grimm Brothers’ folk or fairy tales, though in the first season there are three two-parters (“The Frog Prince,” “Puss in Boots” and “Cinderella”) and one feature-length four-parter (“Snow White”). Season two does away with two- or four-parters altogether.

Although I just said that each episode is based on a Grimm folk or fairy tale, you may be surprised to see “Puss in Boots,” “Bluebeard” and “Beauty and the Beast” among them, since they are known by their French versions. But renditions of these stories were included in the 1812 edition of the Grimm’s Children’s and Household Tales and subsequently removed due to their French origins (the Grimms wanted to include stories that were “authentically” German, but that’s a discussion for another time). I’ll go into more detail when discussing each episode individually, but in short the versions that appear in Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics are based on the ones from the Grimm’s collection, not their famous French counterparts. The reason why this wasn’t known until recently is because English-speaking audiences only had access to the final 1857 edition of the Grimms’ collection, while the first 1812 edition was only made available in English in 2014, via a translation by Jack Zipes. Japan has had access to the 1812 edition long before the English-speaking world had, hence these stories’ inclusion in the series.

When the series aired in America, on Nick Jr of all things, the original soundtrack by Hideo Shimazu was replaced by music composed by Haim Saban and Shuki Levy, which was recycled from the aforementioned series My Favourite Fairy Tales. More egregiously, many of the more violent and mature scenes from the original were cut, and some episodes never aired at all. Only a select number of episodes (including some that hadn’t been aired) were released on VHS and DVD.

Every episode in the series got an English dub, though that fact wasn’t known at the time, because some of the episodes, particularly those from season two, never got any home media release, thus making them lost media of sorts for a long time. The entire series, both its English dub and the original Japanese with English subtitles, was eventually released by Discotek Media in 2021. In a special feature from the Blu-Ray, the Discotek media staff explained that they found the original masters of the English dub. Because the video quality of the masters was in terrible condition, they meticulously edited the episodes to match the audio.

This leads to a larger aspect of the series, and the reason why I wrote this post in the first place. There is a perception among many people that fairy tales are just children’s stories, helped in no small part by the likes of Disney and Co. Though there have been efforts to dismantle this perception by fairy tale fans and, for better or worse, scholars and their proteges, this mindset persists to this day.

But what many people don’t know is that folk and fairy tales were originally meant for both children and adults — in short, audiences of all ages. Many traditional collections of fairy tales (for instance, Giambattista Basile’s The Tale of Tales) contained a lot of crass and bawdy humour chiefly aimed at adults. Even collections like those by the Grimms, which were, more or less, aimed at children and families, contained a lot of violence and dark subject matter.

Or at least, what we consider violent and dark by our current standards.

You see, back then, murder and torture were considered perfectly appropriate ways of displaying retribution to children. So while anything related to sex or bodily functions was considered a big no-no back then (and also today), you could show violence to children if it was done for educational purposes.

For example, in the 1812 edition of “Rapunzel”, the titular character reveals the prince’s nightly visits by asking her guardian why her clothes are getting so tight. The allusion to sex was considered so scandalous that in subsequent editions Rapunzel asks instead why her guardian is harder to pull up than the prince. However, while in the 1812 edition Rumpelstiltskin simply leaves the castle after his name is revealed, by the 1857 edition he instead rips himself in two in his fury.

I mention all this because anime, and Japan in general, has always been less restrictive on what it can show, compared to America. This means that most of the violence and dark subject matter from the original Grimm stories have been preserved (and in some cases amplified) in Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics. The series does not shy away from depicting dark and disturbing scenes, such as children being mercilessly whipped, a man attempting suicide, animals being abused and overworked and (most infamously) a chamber filled with rotting, decomposed corpses!

In other words, when the series goes hard, it goes hard.

The English dub removed or shortened some (though not all) of these scenes. Upon watching the Discotek release, however, I was surprised to discover that some of them (like the suicide attempt from “Bearskin” and the corpse chamber from “Bluebeard”) were kept intact in the dub. This is because the English episodes were further censored when aired on Nick Jr — those that got aired, anyway. For example, some viewers have recalled that the episode “The Coat of Many Colours” was further censored when it aired on Nick Jr, by having any mention of incest be removed. Said mentions are preserved in the Discotek release.

It should also be mentioned that some episodes are light-hearted or comedic in tone. For example, the wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood” is quite clumsy and goofy, rather than the menacing, savage beast he’s usually portrayed as. Likewise, Rumpelstiltskin’s design is quite benign and, dare I say, cute. They are still threatening villains, but more so in their motives, rather than in their designs.

Perhaps the biggest “twist” in their versions of “Cinderella” and “Little Red Riding Hood” is how relatively light-hearted and non-violent they are compared to how other episodes like “Hansel and Gretel” and “Bluebeard” pan out. So expect no toe-cutting in “Cinderella,, for instance, no matter how disappointed you might be by the prospect (I know I am; I saying this sarcastically, of course).

But here comes the big question: To whom is this show exactly for? It’s too violent and mature in places for children (see “Bluebeard”), but also too juvenile and comedic in other places for adults (see “Little Red Riding Hood”). Take “The Marriage of Mrs. Fox”: the subject matter of a husband suspecting his wife of cheating is not something that would concern (and possibly interest) a child, but its over-the-top slapstick and character expressions would not appeal to the average adult either.

And yet that’s also part of the charm of that episode. And the series as a whole.

The question of “Is this for children or adults?” can also be applied to the Grimm’s fairy tales as a whole. There are stories that are perfectly suitable for children (“Snow White and Rose Red,” “Jorinde and Joringel”), and others that will most likely speak only to adults and their dilemmas (“The Faithful Watchmen,” “Godfather Death”). And there are those that speak to both: the magic and wonder for children, the darkness and dilemmas for adults (“Snow White,” “Cinderella”).

The subject of “Are fairy tales for children or adults?” is a complicated one, no thanks to the complicated history of fairy tales. Many adults consider fairy tales too dark and violent for children, so they either tell them more “child-friendly” stories or bowdlerise them altogether. In the introduction to The Macmillan Treasury of Nursery Stories, Mary Hoffman wrote:

“Although I’m not in favour of bowdlerising fairy tales, when I read over the sources for some of the stories here I did find some of the scenes, particularly the endings, to be unnecessarily cruel and violent. Retribution is all very well, but punishments involving beheadings or boiling wolves alive belong to an older order where revenge, rather than mercy, was the dominant mood. So I have taken the liberty, for the young readership of this book, of toning down some of the endings.”

On the other side of the “debate,” if you will, we have adults, especially fairy tale scholars and their disciples, complaining that fairy tales have become too watered-down and that they need to be brought back to their “adult” origins. In the introduction to Snow White, Blood Red (an anthology of fairy tale retellings aimed at adults), Terri Windling made the usual talking points in this regard:

“Although fairy stories have been written down since the art of literature began, it was during Victorian times that fairy tales began to be widely collected and published in editions aimed at children in the forms that we know them best today. (…) Victorian white, male publishers combed through the thousands of tales gathered in the field by scholars and selected those which they deemed most suitable for their children — or they edited and changed the tales before publication to make them suitable. This bowdlerization of fairy tales continued in the twentieth century, reflecting the social prejudices of each successive generation.

“And so we arrive, by the 1950s and 1960s, at the Walt Disney-influenced versions of fairy tales that most of us know today, filled with All American square-jawed Prince Charmings, wide-eyed passive princesses, hook-nosed witches, and adorable singing dwarfs. And so Sleeping Beauty is awakened with a chaste, respectful kiss. And so Little Red Riding Hood is rescued by a convenient woodman before the wolf can gobble her up. And so tales like “The Juniper Tree” are placed on a high and dusty shelf where they are soon forgotten. (…)

“Thus, when we asked the writers in this anthology to take the theme of a classic fairy tale and fashion a new, adult story from it, we were really asking them to work in an old and honorable tradition, adapting these “houses” built of folkloric material to modern use — just as Perrault did, and the Brothers Grimm when they edited and occasionally rewrote the stories they collected in the German countryside.”

But Windling also made clear that she didn’t want “to imply a disdain for the efforts of authors whose books are published as children’s literature.” Rather, Windling stressed that “fantasy should not be limited to the realm of children’s fiction, (and) it should also not be taken away from that ground where it has been nurtured and has thrived throughout the century.” Indeed, Winding and Datlow went on to edit anthologies of fairy tale retellings for children, not just for adults. Windling also noted that a poorly written fantasy story is just a bad story, regardless if it’s for adults or children.

When it comes to whether fairy tale are for children and adults, I think Steven Swann Jones, in his book The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination, has the perfect answer. In the book Jones divides fairy tales into three subcategories:

Tales for Young Children: They feature prepubescent children as protagonists, whose conflicts revolve around proving themselves to be competent members of the family and society (“Hansel and Gretel,” “Little Red Riding Hood”).

Tales for Developing Adolescents: These constitute the majority of folk and fairy tales, in which postpubescent adolescents leave their home, establish a domain of their own and usually find a lover. In short, they concern a developing adolescent’s path to adulthood (“The Water of Life,” “Cinderella”).

Tales for Relatively Mature Adults: They feature mature adults as protagonists and are concerned with the moral and philosophical dilemmas of adult life, such as “fidelity in a marriage, communication between partners, or adjusting to the birth of children”, but also mortality and economical stability (“The Marriage of Mrs. Fox,” “The Faithful Watchmen”).

In addition, Swann notes that about 10% of the entire corpus of folk and fairy tales features middle-aged protagonists, and about 5% features old people as protagonists. Thusly, about 85% of folk and fairy tales features child, adolescent, or young adult protagonists.

So folk and fairy tales can address the ideals and aspirations of not just a given culture, but also a specific age group. Children can use fairy tales to express their ambivalent feelings towards their parents, while adults can use fairy tales to address the challenges they encounter in their work-life. In short, fairy tales were always meant for both children and adults — together or separately — and thus fairy tales can be both for children and adults. Instead of claiming that fairy tales are solely for children or solely for adults, just retell fairy tales for whatever audience you want to. But if you plan on retelling fairy tales for children, take in mind this quote by G.K. Chesterton: “Children are innocent and love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.”

With this in mind, I believe that Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics perfectly captures the overall tone of its source material. Even if the stories aren’t adapted word-for-word from the original source — which is to be expected when a literary work is adapted for the screen — the series still captures the grimm (pun totally intended) and comedic charm of the stories. As Neil Philip put it in Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: “There is cruelty and darkness in Grimm, but there is comedy and light as well.”

But to fully explain why this series has made such an impression on me, we need to touch a bit on the “animation is for kids” discourse. Despite many examples in the past proving the contrary, there is a widespread notion that animation is and has always been a “genre,” rather than a medium, for kids only. And just like with fairy tales, despite numerous efforts in recent years to counter this notion, it still persists. For example, I’ve had an otherwise erudite sociology teacher in high school referring to Persepolis as a film made in “the style of a children’s cartoon,” despite the film being based on a graphic novel and emulating that style.

As a result, every animated project is either for kids or for adults. There are shows like Steven Universe and The Owl House that claim to be kids’ shows, when in reality they’re aimed at a terminally online YA audience, but that’s about it. Even anime is more or less considered a medium aimed exclusively at teenagers and young adults, with its own set of tropes and expectations. I think Andrew Osmond, in 100 Animated Feature Film: Revised Edition, best explained the situation at hand:

“The animated feature has had a long succession of counterculture icons. Yellow Submarine, Richard Williams, Ralph Bakshi, Jan Svankmajer, (Studio) Ghibli, Cartoon Saloon and even The Lego Movie have all been framed as alternatives to the stultifying cartoon establishment of the day. (…) What keeps the field alive is a continuing series of alternatives, not a lone vision. (…)

“Animation fans have asked for decades if an ‘adult’ animated feature could be commercially mainstream — a film not just enjoyed by adults, but aimed primarily at them, perhaps excluding children altogether. Such films have always been made, from Fritz the Cat to Anomalisa, but nearly always on the margins. (…)

“Japanese animation is often cited as containing adult themes. However, most anime films are commercially marginal even in Japan. True, there are domestic ‘blockbusters’, such as Princess Mononoke (1997) and Your Name (that) play differently from Hollywood’s CG mainstream (and are) less reliant on jokes, and have fewer moral binaries. (…)

“However, even (those films) use young protagonists and fledgling romances, as do most anime. It’s rare to find an anime protagonist over twenty, let alone twenty-five. Your Name had wistful interludes, and a story that resonated with Japanese trauma, but it’s still an anime equivalent of Back to the Future (1985). It’s far from the middle-aged concerns of Anomalisa, The Illusionist (2010), The Congress (2013) or Rocks in My Pockets (2014). The chances of that kind of animation reaching the mainstream seem remote; but it’s likely such films will continue to be made, and still find followings.”

That is, unless, you consider Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics. A series that is both child-friendly and mature, both comedic and violent. A series that isn’t afraid to dip its toes into serious subjects, but can also be light-hearted and comedic when it wants to. A series that seems to skirt over the dichotomy of what is acceptable for kids or even adults. More importantly, a series that has shown me, more effectively than any other piece of media could, that animation is a medium that can tell compelling stories regardless if it’s for kids or adults. And it did this by doing both.

To better explain my point, when talking about the Hotel Transylvania films, AniMat (ElectricDragon505) bashes them for being too “cartoony”. The films were directed by Genndy Tartakovsky, who also created Dexter’s Laboratory, and they use a similar cartoony exaggerated style from that show. This is a bad thing in AniMat’s eyes, because to him snappy exaggerated animation is only for Saturday Morning cartoons (and even goes as far as to claim that it’s only used to save money), while feature film CGI animation should be more sophisticated and grounded. He even claims that the use of cartoony animation (or “over-animating” as he calls it) in family feature films is what contributes to the perception that animation is “just for kids.”

Ignoring the fact that Tartakovsky also created Samurai Jack, Star Wars: Clone Wars, Sym-Bionic Titan and Primal — shows that are more serious, mature, and overall less reliant on comedy — AniMat is essentially creating a dichotomy here: that TV animation is comedic and therefore should only use an exaggerated style, and feature film animation is “sophisticated” and should only use a realistic style.

Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics proves that this mindset is reductive: it’s a TV series that has both comedic episodes (“The Marriage of Mrs. Fox”) and dramatic episodes (“Bluebeard”); both styles can coexist and they don’t have to be restricted by genre or medium. (And seriously, who is expecting realism in a film series about Dracula running a hotel for monsters? While animation is a budget-dependent medium, some works have a certain art style by design, not necessity.)

Perhaps I’m being hyperbolic here, but I believe Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classic shows where animation can go if we allow it to flourish without imposing restrictive standards on it. The fact that it’s a series both for children and adults can be seen as a problem by some, and that’s fair, but for me (and I believe for others as well), that’s part of its appeal. It captures the tone and appeal of the Grimms’ fairy tales while adding twists and embellishments of its own.

If I were to have a type of audience in mind when recommending the series, it would be the same as how I would recommend the Grimms’ fairy tales in general: some episodes are perfectly fine for children (“Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Golden Goose”), some are best left for adults (“Bluebeard,” “The Coat of Many Colours”) and some are appropriate for everyone, regardless of age (“Snow White,” “King Grizzle Beard”). If you are a caregiver, it is best to vet each episode before deciding which to show to your child. If you’re just an adult (or even teen) who wants to watch, I’d say dive right in.

But no show is perfect, and this one is no exception. In spite of the high praise I’ve given it so far, this show has its problems. We’ll talk more about that in the following posts, where I talk about each episode in the series and give my thoughts on them. Yes, I had to split this post into multiple parts because it would have been too long otherwise. But, hey, more the fun, right?

If this post and the others will encourage you to check out this series, well, my job is done here. And if you do, I’m curious to know what you think of it. The series is relatively obscure as far as fairy tale media is concerned, but it’s not without its loyal fans, of which I can proudly declare myself as one.

The episode posts will come out… eventually. Hopefully.

References

“Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimm%27s_Fairy_Tale_Classics. Accessed 16 July 2024.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Translated by Jack Zipes. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Grimm Masterpiece Theatre (Gurimu meisaku gekijō) or Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics, directed by Hiroshi Saitō and Kerrigan Mahan, Nippon Animation and Saban Entertainment, 1987-1988.

“Hotel Transylvania 2 - AniMat’s Reviews.” YouTube, uploaded by ElectricDragon505, 5 October 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0i8W4TCFkHE.

“Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation - AniMat’s Reviews.” YouTube, uploaded by ElectricDragon505, 13 July 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QJiymxSiROM.

Jones, Steven Swann. “The Thematic Core of Fairy Tales.” The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination. 1995. Routledge, 2002.

lenlo. “Guest Post: Unearthed Treasure with Firechick – Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics (77/100).” Star Crossed Anime, 25 February 2024, https://starcrossedanime.com/guest-post-unearthed-treasure-with-firechick-grimms-fairy-tale-classics-77-100/. Accessed 16 July 2024.

My Favorite Fairy Tales (Sekai Dōwa Anime Zenshū), directed by Shigeru Omachi and Robert Barron, Studio Unicorn and Saban Entertainment, 1986.

Osmond, Andrew. “Introduction.” 100 Animated Feature Films: Revised Edition. 2010. Bloomsbury, 2022.

Philip, Neil. “Introduction.” Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Little, Brown and Company, 1997.

Windling, Terri. “Introduction. White as Snow: Fairy Tales and Fantasy.” Snow White, Blood Red, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling. 1993. Fall River Press, 2011.