The Discourse on Disney's Snow White (2025)

And why some people are not willing to admit it's bad.

March 21 (or earlier, depending on where you live) marked the realise of Disney’s latest live-action remake, this one of Snow White (1937), the first animated feature film made in colour and sound. No huge expectations there, I’m sure.

March 21 also marked, as Dour Walker (Nostalgia Critic) put it, “YouTube Reviewer Christmas Day” due to the flood of people making review after review of this film, mostly to trash it… but also, for some, to defend it.

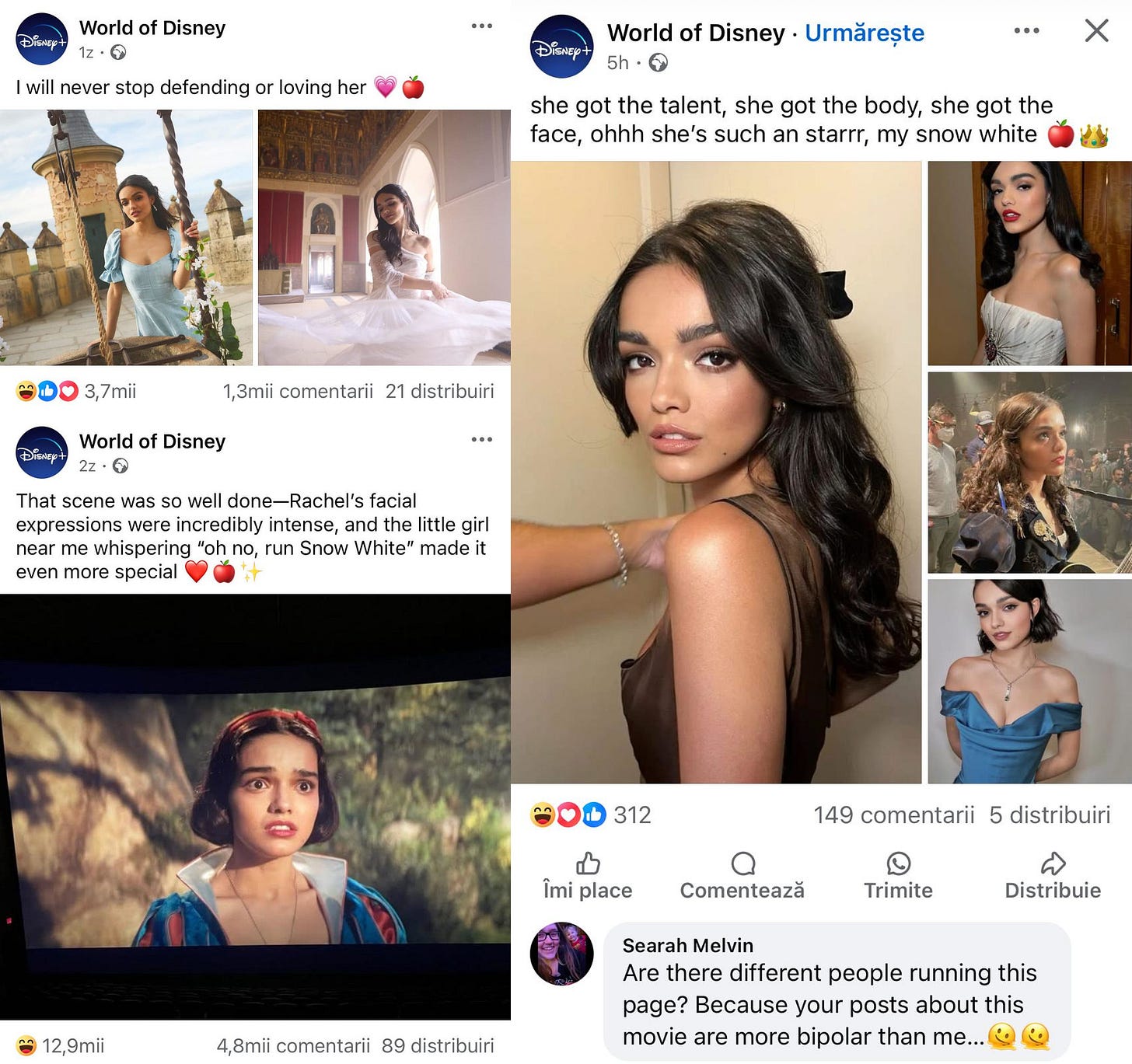

Despite having a lower IMDb score than Dragonball Evolution (2009) (1.6 as of writing), and a 39% Critics Score on Rotten Tomatoes (with a 72% Audience Score, again, as of writing), the film has been defended, perhaps predictably so, by the exact kind of people to whom it was pandering to intended for: the “modern audience.” That is, people who only like a film if it aligns with their political beliefs, while pretending that they do because of its “creative twists.”

Naturally, these people have made narratives around the reception of this film, which, given the current political climate, was to be expected:

Narrative #1: “All the hate is coming from MAGA conservatives who didn’t even watch it, or want to!”

While I’m not denying those people exist (just look at the more negative reviews on YouTube), assuming that every negative review of this film comes from one political party is just a lazy, almost childish dismissal of legitimate criticisms of the film.

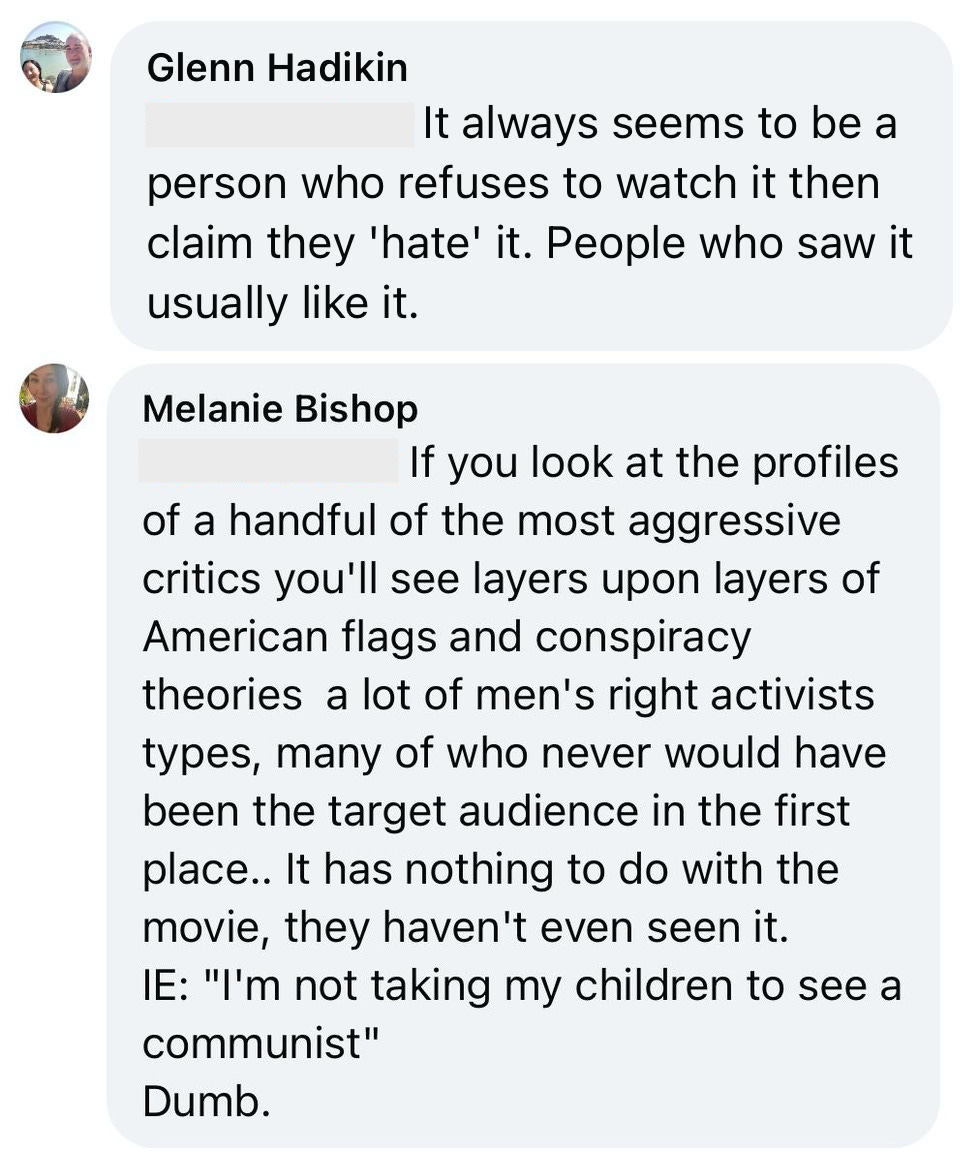

I also took a peek at some posts about the film from a German fairy tale film fanpage on Facebook, which contains news and discussions on the Märchenfilme and other German fairy tale film releases. The same narrative can be found there. I want to highlight here a few comments I saw in one of the posts. For context, the post was outlining the film’s controversies, and someone ranted about the film’s “haters,” as can be seen below (the comments were translated via Google Translate):

The commenter also said that the film was good, actually. Which is fine, of course. Everyone is entitled to their own opinions. This person never actually explained why the film is good, besides listing what they liked and that the film is not a carbon copy of the original, which frankly is the least a Disney live-action remake should be.

Someone responded to the first comment, basically asking (politely I might add), “Don’t you think you’re generalising on those who criticise the film?” In response, the commenter went on the same unhinged rant by using not just Narrative #1, but also:

Narrative #2: “People who are hating on this film are racists and misogynists!”

The other person challenged further, by basically asking, “I’m not denying those people exist, but that’s not true of everyone. After all, the responses to this film are mixed at best.” (And they are, if you look at most critics’ reviews.) The commenter went on yet another unhinged rant, by using:

Narrative #3: “People who had actually seen it like it! Therefore the film is good!”

This person went even further by claiming that they’re in over 50 Facebook Disney groups from various countries, and that most of the people there who had seen it said they liked it. Confirmation bias much? After all, this person only said “those who have seen it,” without mentioning how many.

But there is some truth to this person’s words.

I’m also in (admittedly) one Disney Facebook group (don’t judge), and the responses there from those who had seen it were somewhat mixed: some didn’t like it, but a significant number said that they did. Of those who did, many used phrases like “I went to see it with my family, and my kids loved it,” and “I saw it twice in the theatres.”

And I repeat that this is fine — everyone is entitled to their own opinion. My problem is that many of these statements are followed by comments similar to those above, or that outright dismiss the original in order to elevate this remake. I can’t help but postulate that these people went to see the film with the mindset of liking it no matter what, so that they can declare that it is “better than expected,” while simultaneously “owning” the “haters.” They may also genuinely like the film because it aligns with their personal beliefs, regardless of it actual quality. I expect this reaction to be even more prevalent once the film becomes available on Disney+.

In short, I believe there is an agenda behind the positive reception of this film, just like there is an agenda for its negative reception.

There was another commenter to that discussion who wasn’t as unhinged, but still made excuses for it by using:

Narrative #4: “The original is over 80 years old, of course it had to be updated for a modern audience,” with a dash of “Children of today will automatically like this new version better because it’s modern.”

Never mind the film’s actual quality, of course. Or if it will continue to be relevant even 20 years from now.

The page these comments come from clearly has a bias for this film as well, for it felt the need to make weekly posts about the film’s charts at German cinemas. And wouldn’t you know it, it was first place in its first two weeks! Ignore that it doesn’t specify how many seats were reserved for the film, especially in comparison to other films. Or how much it gained at the German box office. Or that the film has had the lowest box office returns for any Disney live-action remake. Or that, once again, it doesn’t reflect on the film’s actual quality, or if everyone liked it.

While still declaring the film to be uninspired, Simon Dillion simply couldn’t resist taking a swing at the “haters,” as he opened his review with this statement:

“It’s a shame I consider this necessary, but I should state upfront that this is a review of Snow White based on seeing the film at the cinema last night. Therefore, I can speak from a place of authority, unlike the legions of numpties who decided to review bomb it before it was even released.

No matter how much weapons-grade cynicism I feel about algorithmically mandated, artistically redundant live-action remakes of beloved animated features, the most basic principle in reviewing is that first, you actually watch the damn film. That fact seems lost on the plethora of nitwits hellbent on demonising Rachel Zegler. Or Gal Gadot, for that matter, depending on whether their social media bullying bullhorns of choice are misogynistic, racist, antisemitic, or otherwise politically motivated.” (Emphasis my own.)

Here we see an application of Narratives #1 and #2, with a dash of “review bombing” accusations. And while yes, I believe that one should judge a film without political bias — I’m a staunch advocate of that, in fact — it’s impossible to do that in this day and age. Why? Because Modern Disney is now using women and non-white people as a shield against justified criticism for their consistently mediocre products (just look at the discourse on Turning Red and the Little Mermaid remake).

Dillion even makes a call at the end of his review, for the people who had actually seen the film:

“I do recommend challenging any naysayer dismissing the film based on Rachel Zegler or Gal Gadot’s race, nationality, or political persuasions. Ask such naysayers a simple question: Have you actually seen the film?” (Emphasis my own.)

Yes, Dillion, I have. Despite promising myself to never financially support a Disney live-action remake after Beauty and the Beast (2017) (I pirated The Little Mermaid (2023), and I have no regrets for doing that), curiosity got the better of me and decided to watch the film in theatres. On preview night. Meaning that I had to pay extra. I actually watched the film with my mom, in a half-full screening. Therefore I can speak authoritatively on the film. So…

Is the film that bad?

Yes. But also, no.

It’s certainly not worse than Dragonball Evolution. This is where I’d have to agree with the defenders and say that the huge amount of 1-star ratings on IMDb feel like a coordinated attack on the film, and not legitimate criticism.

How does the film compare to the other Disney live-action remakes?

Well, it’s not as offensive as Mulan, certainly not a carbon copy of the original like The Lion King, and not as boring as Aladdin. I’d put it between Peter Pan and Wendy and The Little Mermaid: it feels more like an apology for how “outdated” the original is, but it’s not interesting enough to earn little more than a resounding “Meh.” It’s a 4/10 film, in other words. Maybe 5, if I’m generous.

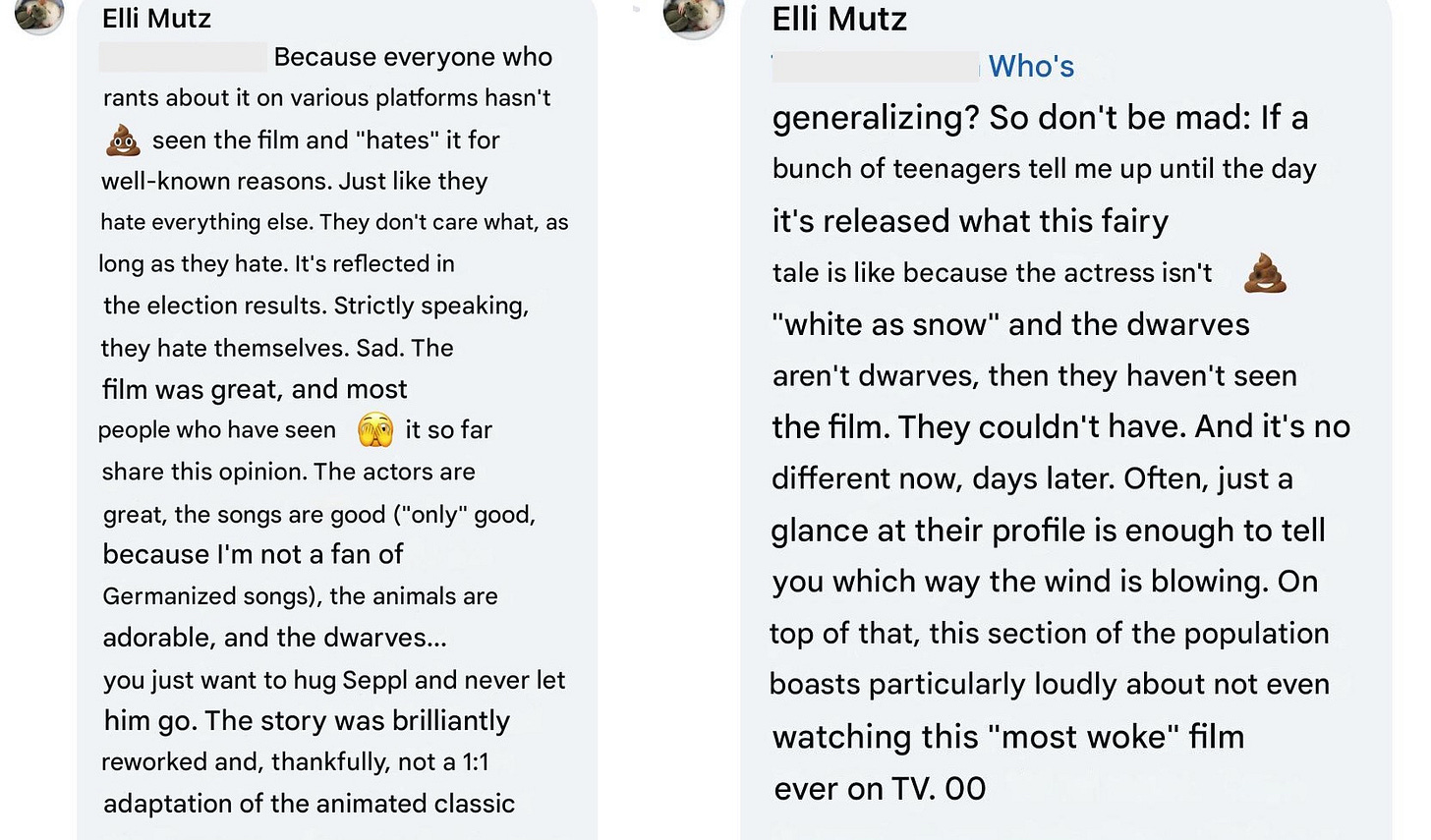

I think that Doug Walker describes the film really well: “It feels like a Disney Film Production with a Disney Channel script.” Somewhat related, Yakubian Ape recently made a post that deftly pointed out how disposable a lot of modern entertainment is, especially if it’s a Netflix production. There’s nothing majorly wrong with it — well, nothing majorly good either — but also nothing outstanding. You watched it, had an okay time with it, and then immediately forgot about it as soon as it was over, having made no major impact on you.

This is also why those from the German fairy tale film page from Facebook were so defensive about the film: because it’s the kind of film they’re used to seeing. TV-tier productions that are entertaining enough, but nothing more. Certainly not Oscar worthy. They’re not meant to push the envelope or make a major impact, but to simply entertain for an hour and a half. To quote from Doug Walker again, “It’s a movie that’s supposed to be talked about not after watching it but while you’re watching it.”

And there’s nothing wrong with that. I’m a sucker for this kind of films myself. There is a time and place for lighthearted, not super complex films. If on one end of the spectrum is Grave of the Fireflies, on the other is My Neighbour Totoro, and both are completely valid types of films that serve different purposes. But I also think that film critic Leonard Maltins, in the introduction to the book Family Film Guide, made a very good point about film criticism and audience expectations:

“Children who have never eaten anything but McDonald’s hamburgers can’t be expected to appreciate filet mignon when they first taste it. They must be educated—or weaned, if you prefer—onto better movies, as well.”

But even if it’s only McDonalds that you want, Doug Walker once again made a very good point about this: “You can have your fluff, you can have your junk food, but even junk food has to taste good.” Just because a film isn’t high art, that doesn’t mean it has to be bad, or that you should lower your standards, or that you have to blindly defend it no matter how objectively bad it is, just because it’s from your favourite genre. In other words, don’t be like this guy:

Of course, the opposite can also be true. If you look at the reviews of the Märchenfilme on Letterboxd, a lot of them — if not all of them — seem to have ridiculously high expectations for these films. They are TV-productions — expecting them to have the same level of finesse as a theatrical Disney production is simply unfair. Judge them for what they are — but don’t lower you standards either. None of the best pieces of media have became the way they are simply because the creators went, “Well, this is good enough! I don’t have to try any harder.”

Still, I haven’t yet talked about why the film is bad, so I’ll briefly do that in bullet points. Keep in mind that some of these points have been elaborated upon in other reviews, so I’ll try not to dwell on them too much:

The first nine minutes of the film (basically its opening) feel really rushed and leave more questions than answers about its setting.

The overall look is the same as all the other live action remakes: dark, muted colours that simply pale in comparison to the artistry of the original.

The film has a bad habit of interrupting the songs with character conversations; it’s repetitive and jarring, and in my opinion could have been easily remedied.

Most of the film’s songs are original; “Heigh-Ho” and “Whistle While You Work” are still here, albeit edited, while the rest are generic pop music you’d hear on the radio and forget about as soon as they’re over. They don’t fit with the original songs, and while they’re okay, they’re not memorable and hummable either.

After the backlash over Rachel Zegler’s comments, the film had major reshoots, and it shows. It feels inconsistent in tone: at times it’s a postmodern revised fairy tale, and other times it’s trying (and failing) to recreate the original.

And the recreations feel more like a rush job than genuine callbacks: a good example is the scene where Snow White runs into the forest, where it only lasts for about a minute in the remake and it has nowhere near the same impact as the original scene.

At this point, I expect some would say, “You criticise the Disney remakes for being carbon copies, but you criticise this one for not being like the original!” Fair point. The problem is that the film tries to have its cake and eat it too: it wants to recreate the original film for the sake of nostalgia, but it also wants to smugly “fix” any aspect that would be considered problematic by “modern audiences.” The result is a film that doesn’t seem to know what it wants to be, and is therefore inconsistent.

As a result of the inconsistent tone, Snow White’s character is also all over the place: at times she sort of resembles the original character, but at other times she is the girl-boss leader that I expected her to be.

The romance between Snow White and Jonathan (the prince replacement) is badly executed and unconvincing: they hate each other and banter at first, and then suddenly they’re smitten with each other. Their romance is very similar to that of Anna and Kristoff from Frozen.

Snow White’s hair and costumes look terrible, especially for such a high-budget production, and this is coming from someone who thinks Rachel Zegler does look pretty (insert Lord Farquaad joke here).

The CGI dwarfs look like reject models from Polar Express (2004); I mostly looked away every time they were on screen.

The film decides to take a lazy postmodernist, nit-picking take on the dwarfs: Sneezy is called Sneezy because he has a nose allergy, Grumpy is grumpy because he feels misunderstood, Doc is a “doctor of rocks,” and Dopey isn’t actually dopey, he’s just afraid to speak up. The film doesn’t do anything particularly clever about this besides just pointing it out.

Related to the above: there is a character arc for Dopey, in that he learns to speak up, but just like the romance, it’s badly executed. Snow White teaches him how to whistle, as a way of expressing himself, and then later, after she is revived, he starts speaking out of nowhere. As someone who had a speech impediment as a child, this is not how it works, and it almost feels like it veers into ableist tropes. So much for being progressive.

Those “seven magical creatures” (see picture below) are still in the film, as part of Jonathan’s troupe of bandits, but it’s obvious that many of their original scenes were cut, because none of them get any screen time or development, except for the guy with dwarfism.

In this film, Jonathan is a Robin Hood-type figure who leads the group of bandits as a form of resistance against the queen. Not only does it feel like it comes from a completely different film, but because of this film’s inconsistent tone, this subplot barely gets any proper development.

Speaking of being progressive, Snow White is still kissed by Jonathan while being unconscious, clearly a reshoot after the backlash. The jokes write themselves.

The film’s finale is anticlimactic. After being revived, Snow White walks into the kingdom, looking like (as one kid in my audience put it) Little Red Riding Hood, alone and unarmed. Despite not having seen her for years, the subjects immediately recognise her and stand beside her against the queen. And how does she win the day? By telling the guards their names and past professions before they were recruited by the queen. And somehow, that’s enough to earn their trust. How she remembers all of their names is beyond me, but that’s what happens when you rush out your film script.

Defeated, the queen runs back to the mirror, who declares that Snow White is the fairest because she is the most just. The queen smashes the mirror in anger, turns into some sort of black glass statue, and is sucked into the mirror, who then rearranges itself. All the while, Snow White witnesses the whole scene.

Most of the other aspects are just okay, but not particularly remarkable. Rachel Zegler does an okay performance and singing (like Hailey Bailey, at least she can sing), but it’s nothing outstanding. At least she seemed to try her best with what she was given. Gal Gadot is equally just okay, which was admittedly a disappointment for me, as I expected her to give a hilariously wooden performance, like she did previously. Here she is just mildly wooden, but not memorably so. All the other actors equally did just okay.

Some of the film’s defenders claim that the film isn’t as “woke” as it could have been, and on the surface it may seem that way. I’d argue that it is, but that wouldn’t be a problem in and of itself if it didn’t interfere with the film’s overall quality. Some of these “woke” elements are sneakily hidden in the film. The queen is not some tragic, misunderstood villain… but she’s basically a walking metaphor for politicians like Donald Trump, as Rachel Zegler revealed in an interview for Allure. The seven dwarfs are kept in the film, even as CGI figures, but the word “dwarf” is never used in the film, and there’s also the needless deconstruction of their names.

In the romantic duet between Snow White and Jonathan, “A Hand Meets a Hand” — which is where they abruptly switch from haters to lovers — they sing the lyrics: “But if there’s a world where you wake me/Promise to wake me with a kiss.” This is meant to imply that the kiss Jonathan gives to the unconscious Snow White at the end is consensual, but I’m not sure if this is enough to justify it.

And then there’s the “progressive” elements that are not so sneakily hidden. Snow White is named after a snowstorm, not because her skin is as white as snow. Snow White makes the dwarfs clean their house in the “Whistle While You Work” sequence, while she simply bosses them around like she owns the place. Never mind that she broke into their house without their permission, and the least she could do was help them clean the house.

In general, the film tries very hard to avoid any aspects that would be seen as “outdated” or reinforcing gender stereotypes, and nowhere is it more obvious than in the poisoned apple scene. After she captures Jonathan and learns about Snow White’s whereabouts, the queen sets her plan into action. While her transformation into an old hag and the brewing of the poisoned apple were two separate scenes in the original, here they are combined into one rushed montage, lacking the original’s momentum, and sung over a reprise of “All is Fair,” the film’s villain song.

She goes to the dwarfs’ cottage, where Snow White is not baking a gooseberry pie, but preparing to go searching for her father, whom she thinks has been captured. The old woman is not there to sell her an apple, but to tell her that Jonathan has been captured, and gives her an apple for her journey. Even though one would eat such a snack during a journey, and not before it, Snow White immediately bites into the apple. She collapses… but not before the queen tells her that her father is dead. All the while, the animals rush to the dwarfs to alert them of the danger, again lacking the momentum of the original. The scene overall focuses less on the actual apple offering ritual and more on the drama surrounding the improvished kingdom.

Many of this remake’s twists to the classic story have been done before by other screen adaptations of “Snow White” — and better too. Both Snow White and the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror feature an empowered, “modern” Snow White: in the former she leads a war against the queen, and in the latter she joins the dwarfs’ Robin Hood-esque band to rebel against the queen’s tyrannical rule. In Once Upon a Time Season 1, Snow White is a bandit running away from the queen. The 2019 Märchenfilm Snow White and the Magic of the Dwarfs has a tomboy Snow White who also learns about her father’s death after being revived and wages against the queen with the dwarfs and the prince, but in a much better executed climax. There are also other film and TV depictions of Snow White (Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics, Faerie Tale Theatre, Snow White: A Tale of Terror, The Legend of Snow White, Red Shoes and the Seven Dwarfs) where she is not a modern, “strong” leader (at least in the traditional sense) but nonetheless she’s a much more interesting and developed character.

And this is not even counting the adaptions from the literary world.

Over 80 years have passed between the 1937 and 2025 Disney versions of Snow White, and in that time many other versions have been made that reinvented and expanded upon the original story in various ways. The 2025 remake has taken some of these twists, blended them together without any attempt to make them cohesive or unique, and awkwardly forced them against the backdrop of the original 1937 film. The result is a derivative, insincere, conflicting film that tries too hard to please both fans of the original and “modern audiences” to the detriment of the story, on top of suffering from the same problems that have plagued all the other Disney live action remakes.

If I were to compare this to The Little Mermaid (2023) — the other remake I talked about on this Substack — I’d say that the former is better. While it is essentially a carbon copy of the original, at least it is consistent in its tone and story. Or at least more so than this film.

Sure, Snow White (2025) is harmless enough and, like I said, not the worst thing ever. But there’s nothing particularly memorable or outstanding about it either, especially when compared to the myriad of other Snow White adaptations out there. We shouldn’t settle for the bare minimum just because it is a “modern” reimagining. Especially when it is a remake of a film that has made history.

Is Snow White (1937) an outdated film?

Comments like the one above show that many of the remake’s defenders haven’t watched the original film in quite some time and rely solely on Rachel Zegler’s (misinformed) comments as their point of reference. I believe this is what has fuelled many of the terrible Disney “hot takes” that flooded the internet throughout the 2010’s: people remember parts of the film, hear someone’s distorted, agenda-driven description of it, and — without bothering to rewatch it — take the words of the “experts” at face value and label the film “problematic.”

Part of the blame, in my opinion, lies with the now thankfully discontinued “Disney Vault” system, which made it difficult for people to access these films for years, leaving them with no option but to rely on other people’s words.

Of course, there are also people who did take the time to rewatch the film and still came to a similar conclusion, declaring it outdated. And it is to these people that this section is dedicated.

One aspect that a lot of people seem to have forgotten is that every piece of media is a product of its time, meaning that it reflects the attitudes and tastes of the period in which it was made. This is true for every piece of media — including those that are being made today. What matters is that said media is well-made, and I’d argue that Disney’s Snow White, the 1937 original, is a well-made film.

To be sure, it is a product of its time and does contain some aspects that are outdated by today’s standards. But aside from Grumpy’s comment about women being poison (made when he first meets Snow White and clearly walked back by the end), and the scene of Snow White praying (feels surreal to see this in a Disney product, doesn’t it?), most of the outdated aspects come from the nature of the film itself.

In my essay on folk and fairy tales, I criticised a take made by Jane Yolen in which she claimed that Disney’s Snow White “sentimentalises” the original story and flattens the characters into “cartoon caricatures.” While this is technically true, it also shows that Yolen is a literary critic, not a film critic, as she seems to have no idea how films work in general (she compared the film to Trina Schart Hyman’s picture book version). Above all, she seemed to ignore the historical and artistic context behind the film. As I argued in my piece: “Disney’s 1937 film might appear simplistic by today’s standards, but at the time, its focus on emotional drama was groundbreaking, certainly more sophisticated than the comedy-focused cartoons that preceded it.”

The film came out in 1937, meaning that its only point of reference was gag-based cartoon shorts like Three Little Pigs, The Old Mill, and The Skeleton Dance. Those shorts were less concerned with plot and character development and focused more on creating gags and experimenting with animation in under ten minutes. This is why Snow White (1937) has scenes that might seem pointless from a modern narrative standpoint, such as the hand washing sequence and the dwarfs looking for the intruder — or are they?

While modern films focus more on plot and character development, this one focuses on the “emotion” of the scenes: Snow White running in fear through the woods, the dwarfs searching anxiously for the intruder, and the joyous dance between Snow White and the dwarfs. These scenes may not advance the plot in a technical sense, but they do establish Snow White’s growing bond with the dwarfs. This all culminates in the mourning scene near the end. Even though we know Snow White will be revived, we still feel the dwarfs’ sorrow deeply because we’ve seen how much she came to mean to them.

This film is a perfect example of the emotional logic that permeates fairy tales, another aspect I touched upon in my essay. It doesn’t give you what your mind wants to see, but what your emotions want to see. As a result, character motivations and development come naturally from emotion rather than exposition.

This is yet another aspect in which the 2025 remake fails: it’s more interested in deconstructing the original film’s so-called “outdated” narrative than in developing a meaningful relationship between Snow White and the dwarfs. There’s a vague attempt to have her connect with Dopey, but it feels more like a setup to question his name than a genuine emotional bond.

There Will Be Fudd made an excellent video explaining the context behind the film, why it works on a narrative level, and why its values and themes are just as relevant today as they were back in the 1930’s:

But what about the prince? Is he “literally stalking” Snow White? No, he isn’t. Weird, weird, I know, but allow me to explain.

The film relies on emotional logic to advance the plot, and the same goes for the romance. On the surface, it appears contrived and superficial. Snow White sings in the well about wishing for someone to love her — not romantically, mind you, just someone to love her. Considering that she has no one but the wicked queen for company, it’s understandable why she’d want love and affection from someone, anyone. She gets that with the forest animals, the seven dwarfs, and finally with the prince. But let’s get back on track.

Snow White sings in the well, the prince overhears her and goes over the wall to meet her. Snow White runs away into the castle when she sees him, but it’s clear from her reaction afterwards that it’s not because she fears him, but because she feels embarrassed to be seen in her rags. Why else would she send a white dove to him as a symbol of her love?

The romance is told entirely through visuals and emotional cues, so even though we know very little about the prince, we feel a genuine love between him and Snow White, which is enough in this kind of film. Unless you’re someone who approaches stories like this with a cynical mindset, which the defenders of the 2025 remake clearly do.

As mjtanner pointed out, the prince was originally going to have a bigger role in the film, instead of just appearing at the beginning and end. His role was eventually reduced because the animators still weren’t confident enough in drawing male figures. This is also why the first Disney princes had less screen time — and therefore less development — than the princesses. (And in case you’re wondering, those scrapped ideas were repurposed in Sleeping Beauty.)

In regards to the infamous kiss… I’ll be honest, I always found the prince falling in love with what he initially believes to be a dead girl to be super creepy and gross, which is (partly) why I cut him out of my own version of the story. But in the context of the 1937 Disney film, it is surprisingly not creepy and gross… maybe a bit weird though.

This is where you can tell if someone actually watched the original film, because it clearly states, in (an out-of-place) title card, that the prince had been searching for Snow White. When he finally sees her on the bier, his reaction is clearly that of someone who believes she is dead. So he gives her a goodbye kiss… which, as I said, is a bit weird, but that’s how some people say farewell to their loved ones. He certainly didn’t plan to do anything with her body, much less expect her to come back to life.

And while not a major point of criticism, I still want to address this stupid complaint: “The prince is clearly an adult and Snow White is a 14 year old. Therefore the romance is creepy!”

In the Grimms’ tale, Snow White is seven when the main events take place, but in the Disney film, her age is never stated. She could be a young adult for all we know. She certainly looks like one to me. This complain might have some weight for other Disney films like Sleeping Beauty and The Little Mermaid, where the characters’ ages are stated clearly (both 16), but this is not the case with Snow White. The film never specifies her age. Stop taking made-up internet theories as fact and actually watch the film.

I’m not going to pretend that the film is an untouchable masterpiece, or that it has the most complex plot and characters. But for what it is — the first animated feature film made in colour and sound — it is a major achievement, but most importantly, an enduring classic. It is clearly a film made with passion and heart, and when a film is created with a genuine love, it will continue to resonate and remain in the human conciseness even 80 years after its release.

Which is more than I can say for many of the films being made today. Am I right, Rachel Zegler?

Rachel Zegler has a narcissism problem

In hindsight, I think I was a bit too harsh on Halle Bailey in my post on The Little Mermaid (2023). While the opinions from that piece haven’t really changed, and I think Bailey had been a massive yes-man (yes-woman?) for Zegler during the whole controversy (which I’m not going to reiterate here because it’s public knowledge at this point), there wasn’t anything majorly wrong that she had said and done either.

If she had made a few disparaging comments about the original film, they were few and far between, and only in the context of virtue signalling about “fixing” the original. This is common practice among Disney remake lead actors. Other than that, she has, to her credit, never done anything to deserve public ire. She even had the good sense of acknowledging that the racism she had received over her casting as Ariel was nowhere near on the same level as the racism her grandparents has experienced. This is where one can tell she and her sister had Beyonce as their mentor.

The same cannot be said about Rachel Zegler.

I want to reiterate that I think Rachel is a decent actor and singer, and that I do not condone any hateful attacks towards anyone, regardless of who they are or what they represent. If Rachel has received any attacks as a result of this post, whoever did it is officially disowned by me.

At the same time, though… I genuinely do not understand why some people are acting like Rachel fixed world hunger or something. She is one of the most obnoxious people I’ve ever seen, and an actual walking stereotype of the self-obsessed, social-justicey twenty-somethings who give Gen Z a bad name. And I say that as someone who’s around the same age as Rachel.

The people defending the 2025 remake (and by extension Rachel Zegler) are claiming that she’s been unfairly attacked by racists and misogynists who hate seeing non-white strong women in leading roles. That’s certainly the narrative Rachel has gone with as well. And if the situation had been similar to Halle Bailey’s, this post would have ended here.

But it’s wasn’t just due to her race and sex.

It was due to her predictably narcissistic and woefully unprofessional behaviour, which had finally came back to bite her.

In an interview with Variety, Rachel said, in her usual weak attempts at sarcasm and virtual signalling:

“It’s no longer 1937. She’s not going to be saved by the prince, and she’s not going to be dreaming about true love — she’s dreaming about becoming the leader she knows she can be and the leader that her late father told her that she could be if she was fearless, fair, brave, and true."

This prediction turned out to be mostly true, especially the last few words. The remake’s mantra lies in Snow White being “fearless, fair, brave, and true” — never mind that ‘fearless’ and ‘brave’ mean the same thing.

In another interview, with ExtraTV, Rachel also said, rather pathetically:

“The original cartoon came out in 1937, and very evidently so. There’s a big focus on her love story with a guy who literally stalks her. Weird! Weird! So we didn’t do that this time. We have a different approach to what I'm sure a lot of people will assume is a love story just because we cast a guy in the movie: Andrew Burnap, great dude. (…) All of Andrew’s scenes could get cut, who knows? It’s Hollywood, baby!”

Way to insult your co-star in your weak attempts at humour.

I’m sure the initial plan was to have no romance at all, but due to the backlash this comment has created, the film added a rather unconvincing romance, as I explained above. As for the “different approach” in what “a lot of people will assume is a love story”… have you read any fairy tales? Inter-class couples are pretty common in them. Heck, even certain Disney films have them: Beauty and the Beast, The Princess and the Frog, and Tangled! Just because there’s not a prince, but a Robin Hood-type commoner, doesn’t mean it’s “unique”.

In yet another interview, this time with Entertainment Weekly, Zegler admits that she hates the original film and finds it too scary:

“I was scared of the original version. I think I watched it once and never picked it up again. I’m being so serious. I watched it once, and then I went on the ride in Disney World, which was called Snow White’s Scary Adventures. Doesn’t sound like something a little kid would like. Was terrified of it, never revisited Snow White again. I watched it for the first time in probably 16, 17 years when I was doing this film.”

In many ways, Rachel isn’t doing anything different from what other Disney live-action actors have done: making disparaging comments about the original film and expressing enthusiasm about “fixing” it. But while the others said it with some degree of class and professionalism, Rachel’s obvious lack of PR training — and her usual brand of Gen Z entitlement — only worsened the situation. It also made Disney’s disregard for their own legacy far more transparent, and people grew tired of it.

mjtanner pointed out that this was not Rachel’s first rodeo. When asked why she wanted to star in Shazam! Fury of the Gods, Rachel said that it was for the money. And maybe, perhaps, because she was a fan of the first film too, but definitely for the money. This did not sit well with fans of that film either.

In this sense, you can thank Rachel for unintentionally bringing the stream of Disney live action remakes to a potential end. But how can you interpret this statement she made about starring as Snow White, during the SAG-AFTRA strike, as anything other than entitlement:

“If I’m gonna stand there 18 hours in a dress of an iconic Disney princess, I deserve to be paid for every hour that it is streamed online.”

Yes, she deserves to be paid — because it’s her right as an actor, not because the audience owes her anything. Never mind that being paid per streaming hour isn’t how the system works; this kind of public statement is simply unprofessional and absolutely not how you market a film. It comes across as being ungrateful for the role she was given and dismissive of both the original film and its fans, all in service of airing petty grievances.

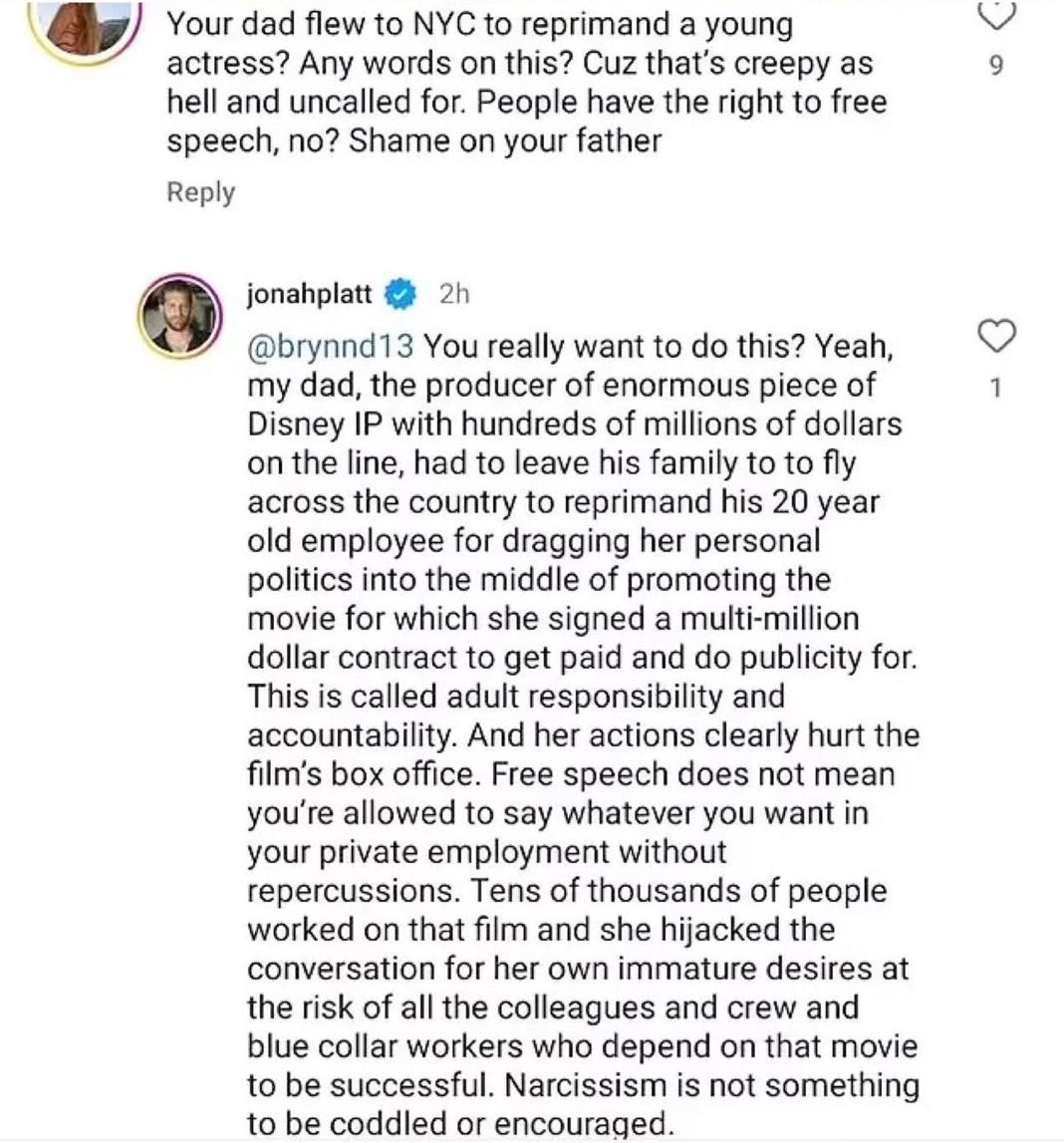

Jonah Platt, son of the remake’s director Marc Webb, said as much in a now deleted Instagram comment:

The backlash (or “hate,” if that’s how you like to call it) made Zegler tone down her comments, while still playing the victim on occasion. When the film finally released, for example, she had this to say:

“To everyone who hates when I win, the Winged Victory came to the Louvre in pieces. And people still line up to see her. And I can only hope that despite my flaws, and despite my cracks and my breaks — and there are many of them —”

She’s clearly on the verge of tears as she says this. At this point, she pauses and stares into the corner, seemingly contemplating, “Is this really what I should be doing? Am I the problem here? Is it really worth it? Yes, of course it is! It’s those racist bigots who hate strong women who are the problem — not me!” Because she ends by saying:

“— that at every premiere, and everything I do, people will wait in line to see.”

Except, many did not. Because the film had the lowest opening for a Disney live action remake. And, as of writing, the box office earns are still fairly low. But anything to own the haters, amirite?

But this is not the end of the video — only half of it. She goes on to say:

“The dumba*s things I’ve said, I don’t absolve myself from that. I’m not sitting here being like, “I’m 21, please forgive me,” like, the stupid sh*t I’ve said and done is stupid sh*t. But I just wanna say, in my personal life, I intend to move forward with a lot more grace for myself, as I grow. There’s a lot that I don’t know. And I won’t know it until I learn it, until I feel it, until I understand it, until I can see it in my hands and say, “I am not broken.” I am just learning. My break is not my end.”

Good for her for having some genuine self-reflection and willingness to grow from this experience. It remains to be seen, however, if she’ll go through with that.

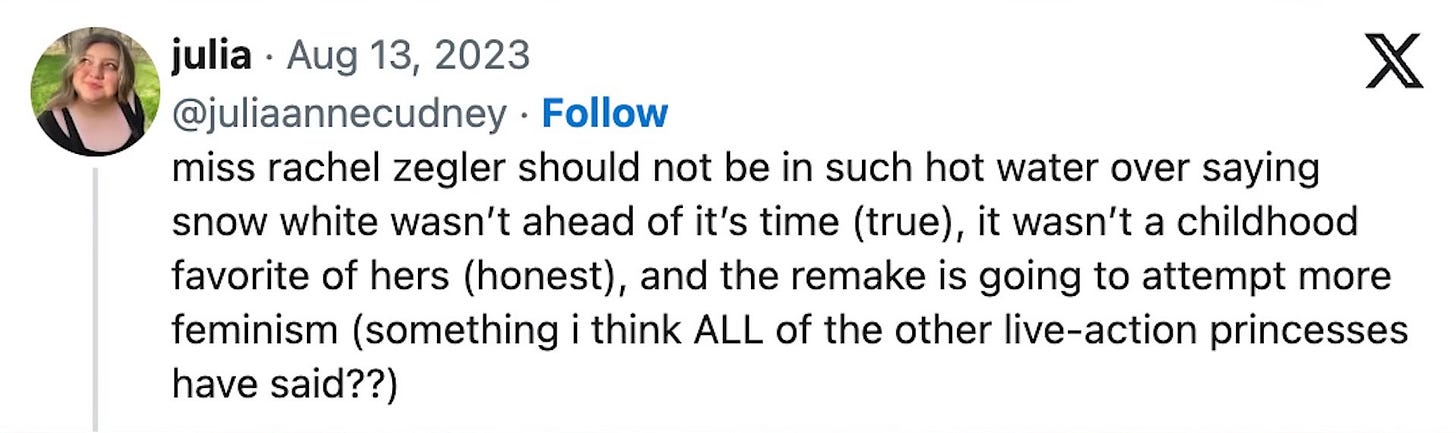

Still, none of that has stopped people from blindly defending her “stupid sh*t,” as perfectly exemplified by this tweet:

Oh boy, where do I begin?

Firstly, like I said, the original film is a product of its time, but this tweet displays an annoying tendency from the “modern audience” to automatically love any new piece of media, simply for being “ahead of its time,” and to automatically dismiss any old piece of media for not being “progressive” enough. Quality be damned, amirite?

A good example of this is the show Scott Pilgrim Takes Off. The “fans” have discarded the objectively superior and better written graphic novel series in favour of the new shallow series, basically treating it as the new canon, and making every excuse under the sun for its flaws, simply because it’s new and “up with the times.” I wonder if twenty years from now a new take on Scott Pilgrim will come out and make these “fans” hype it up and discard Takes Off, simply for being the “new” version.

The original 1937 film will continue to be a classic. The 2025 remake will only be remembered for its controversies.

Secondly, rejecting romance altogether is not a feminist trait. Feminism, at its core, should be about allowing women to make choices for themselves. These choices can include pursuing a relationship, and therefore romance. It’s when you’re forcing women to take only one path in life that’s the problem. Going to the extreme, by telling women that they should not pursue romance, because otherwise they’ll be “settling down” and “losing their independence,” is not feminism.

Of course, romance should not be the only ideal in life, but we shouldn’t reject it altogether either. This is one of my issues with certain pieces of media like Greta Gerwig’s so-called revised Little Women (2019): it presents a false dichotomy between being “independent” and “settling down.” Why can’t it be both? Why does it have to be a mutually exclusive option? My own mother did both, and she has an adoring family and a successful career. Heck, Disney’s The Princess and the Frog showed that it is possible!

My biggest issue with the feminist discourse surrounding Disney and fairy tales in general is that in their efforts to dismantle one harmful dichotomy (either beautiful virtuous princess or ugly wicked witch) they have created a new, arguably worse one (passive victim or strong warrior).

One of my favourite characters growing up was Alice of Wonderland fame. She wasn’t a doormat — she always spoke her mind and took action — but she wasn’t some warrior leader that single-handedly dismantled some regime: she was just a character. Insisting that there are only two templates for female characters — victim or warrior — is very limiting and unimaginative. Variation is key here.

When Rachel Zegler smugly said that the remake might do away with romance because it’s “outdated,” many people found that it echoed the same anti-romance sentiment that modern feminism has been pushing. The backlash this has garnered — including from Gen Z — proved that people are fed up with this reductive way of thinking. Stop shaming girls for pursuing romance or rejecting it. As for the other live action Disney princesses doing this kind of feminism… the same point applies to them too.

But what gets me the most is Julia’s third point, that Zegler “should not be in such hot water” over her honest comments. In order to respond to this claim, I’ll point to another big recent fantasy production: Wicked.

It is fairly common knowledge at this point that Ariana Grande, who plays Glinda in the film, is a huge Wicked fan. She jumped at the opportunity to star in the film adaptation, and when she was cast as Glinda, she promised she’ll “take such good care of her.” Take care of her she did, as she reportedly turned down singing a Hip-Hop rendition of the song “Popular,” because she wanted “to be Glinda, not Ariana Grande playing Glinda.” And the results speak for themselves. Not only was Wicked financially successful, but it was also a well-received film. If even people like the Critical Drinker conceded that the film is good for what it is, you know you did right.

And it’s not like the film hadn’t been broiled in plenty of controversies before it was released. From Cynthia Erivo throwing tantrums over a fan-edit of the film’s poster by claiming that it’s “erasing” her, to the doll packages accidentally linking to an adult website, to those bizarre press interviews that have been endlessly mocked online.

So why was the film successful regardless? Because of one simple trick that seems to have been forgotten by a lot of people these days: respect for the source material. Both the producers and the actors put a lot of effort in honouring the original Broadway show, and as a result the film is actually enjoyable and, above all, sincere.

That sense of respect and sincerity is missing from Snow White (2025), and, for that matter, all the other Disney live action remakes. There’s no genuine desire to honour the legacy of the original film, only to “fix” its perceived flaws while tossing in surface-level references for nostalgia’s sake.

But the million dollar question remains: why agree to play the lead in a remake of a film you openly don’t like? Sure, we all work for the money — that’s a fundamental part of life — but there should be some degree of passion and dedication as well, shouldn’t there? If you’re going to do a job, ideally it should be something you care about. When there’s no passion or creative commitment, the final product speaks for itself — and in the case of this film, it absolutely does.

So why take the role?

The Snow White of the remake is, at her core, your standard modern feminist hero. Her main goal is to free the people from the evil queen’s oppressive rule. And while there’s nothing inherently wrong with that kind of character, it’s simply not what Disney’s rendition of Snow White was ever about. The original character wasn’t some revolutionary leader; she was a kind, gentle soul who cared for others not because she wanted power, but because it was in her nature.

Rachel Zegler is your average social justice Gen Z type, in many ways similar to the Snow White in the remake. Which brings us to the real answer: Disney wanted to reinvent Snow White as a girl-boss revolutionary leader — and Rachel fit that mold.

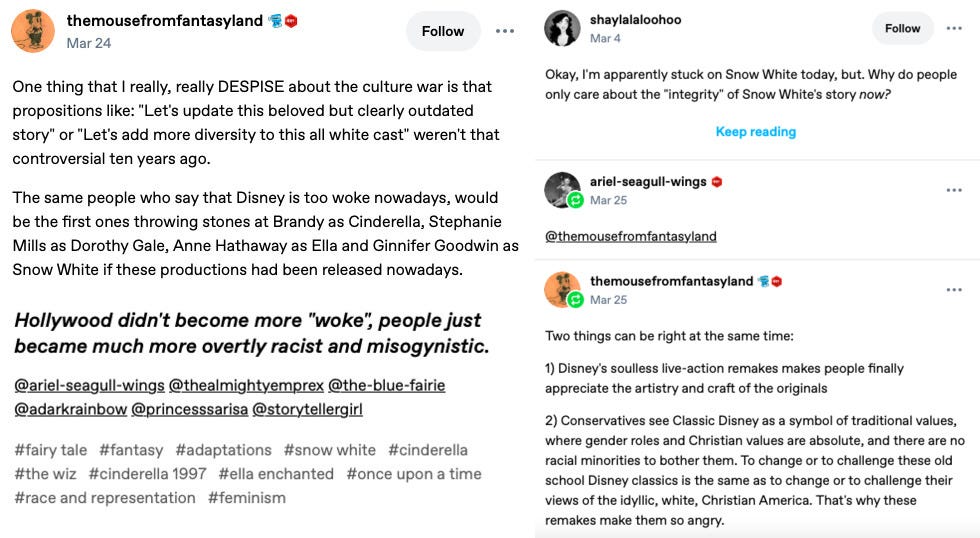

The politicisation of media criticism

One of the worst outcomes of the culture wars is a phenomenon I’d like to call “the politicisation of media criticism.” Simply put, it’s when someone’s opinions of a piece of media is clearly influenced by their personal politics, not by the work’s objective quality. And while media criticism is always going to be somewhat subjective — different tastes, different views, after all — there’s a clear bias in how media is discussed and received today that simply didn’t exist before the rise of the culture wars.

While this trend is more prevalent among left-wingers, right-wingers are not immune from it either. One example is the reaction to the initial trailer for The Minecraft Movie. Some people (conservatives basically) labeled the film “woke” simply because a black woman was part of the cast. Never mind that the film doesn’t delve into racial politics, or that she isn’t even the only non-white character. She’s a black woman and that’s enough to automatically dismiss the film as “woke” and therefore bad. This sort of knee-jerk reaction isn’t criticism — it’s just lazy outrage.

And perhaps because of that, left-leaning reviewers resort to automatically declaring a piece of media good not because it’s particularly well-made, but because it aligns with “progressive” values (however you define them) and/or pisses off conservatives. An example is the mediocre and forgettable (and visually unappealing) Pixar miniseries Win or Lose. After it was reported that a character’s trans storyline had been removed, left-wingers rushed to defend the series, declaring that it is “surprisingly good.” I’ve even seen one person (who shall be unnamed) compare it to Peanuts, which frankly does a disservice to Charles Schulz, but I digress.

It has become a common pattern at this point: conservatives see something that might be “woke” and instantly call it bad, actual quality be damned. In response, left-wingers rush to defend it and declare it good, actual quality be damned. Both sides end up reacting to each other more than actually engaging with the media itself.

Where the two camps differ (besides their ideologies) is in how they treat media aligned with their views. While the right is certainly not immune to making terrible media (Mr. Birchum anyone?), I rarely see conservatives insist something is great just because it matches their views. Sure, you’ve got stuff like Sound of Freedom and God’s Not Dead, but those are the exception, not the rule. There’s also characters like Homelander from The Boys and Ken from Greta Gerwig’s Barbie that are clearly meant to be satirical critiques of right-wing ideals, but they are surprisingly popular among conservatives. Maybe they’re willing to take the joke, as long as it’s entertaining and well executed?

But the left? There’s a laundry-list at this point of objectively flawed and mediocre media that’s defended simply because of its “progressive” values. My Adventures with Superman, while not terrible, suffers from rushed pacing and underdeveloped relationships. Yet it’s praised largely because of its racially diverse cast and Tumblr-esque sensibilities — complete with a “soft boi” Superman and a superficial anime aesthetic. Elemental is one of the most derivative films I’ve ever seen, both as a romantic comedy and as a Pixar film, but because it deals with multiculturalism and a not-so-metaphorical interracial couple, plus it being basically a self-insert of the director’s own personal experiences, it’s suddenly “better than expected.”

There are rare moments when the product is so objectively bad that even those it panders to can’t defend it. I’m referring here to stuff like Velma and High Guardian Spice. But even in those cases, the left practically scrambles for explanations for why it’s bad. They call it “sacrificial trash,” claim it was made bad on purpose, insist it’s a right-wing psyop… take your pick. Anything but acknowledging that maybe prioritising identity politics over storytelling might be part of the problem. Instead of taking responsibility and learning from failure, the response is often finger-pointing and excuse-making. Just like bratty toddlers.

Disney’s Snow White (2025) is no different. The right hates it because Rachel Zegler is in it, and the left is willing to downplay or outright ignore any of its flaws, simply because of its (seemingly) progressive values. The fact that the latter feels the need to denounce the “haters” while praising the film (as shown at the beginning of this post) is a clear giveaway. Never mind that Snow White’s character is inconsistent, she’s a strong opinionated woman and that’s what matters. The deconstruction of Dopey’s name is unnecessary and pointless, but he’s so cute! The songs aren’t forgettable, they’re total bops, I’ll definitely still be listening to them four months from now.

It’s gotten to the point where I can effortlessly predict someone’s opinions on a film — without even watching or reading the review — simply by knowing their personal politics. I hate this. I really do. I hate this because we’re no longer engaging with the work itself, we’re just virtue signalling and defending our “tribe.” I hate this because media criticism has become a political battleground, rather than something we can approach in good faith. I hate this because there’s no longer room for insight and genuine dialogue, just a flood of predictable, partisan takes.

There are people (left-wingers really, as seen above) who claim that people have become more conservative, more misogynistic, more racist, etc. And they are right. Some people are becoming more xenophobic. And do you know why this is happening? Because rather than making good, well-written media that happens to include characters from marginalised groups, studios and creators often use those characters as a shield against criticism. And when someone questions the quality of the work, they’re met with accusations of being an “-ist” or a “-phobe,” or shut down with emotionally charged dismissals.

Now ask yourself: is this really how you effectively change people’s minds? Or is it more likely to make them double down? It’s the latter, of course, because do you seriously believe people are going to respond well to being insulted, dismissed, or told that any disagreement is inherently hateful?

The political right has recognised this and used it to their advantage. They’ve given people a space to voice their frustrations without shame or judgment. But in the absence of balance or nuance — and stuck in ideological echo chambers — some of those reasonable frustrations have devolved into genuine xenophobia and radicalisation.

In their pursuit of moral purity, the left has inadvertently contributed to this growing radicalisation. By framing all dissent as bigotry and hate, they’ve pushed many people further away. But instead of reflecting on their mistakes and taking responsibility, the response each time is finger-pointing and excuse-making. Just like bratty toddlers.

If the left wants to see real, positive change, they’ve got to take a good, hard look in the mirror, seriously reconsider their ideas and strategies, and implement them effectively. Because screaming louder, assigning labels, and shutting down conversations hasn’t worked and will never work unless a serious overhaul happens.

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that I saw the remake with my mother. She’s just your average person, unaware of the online culture wars, simply happy that her son invited her to go see a film together. When the film ended and we stepped out of the cinema, I asked her if she liked it. She said she did, but she seemed distracted. Her mind was elsewhere, clearly on everyday concerns that mattered more than a supposedly bold, modern remake of a classic.

Because at the end of the day, we are fighting over mediocre, forgettable films. Until we recognise that and see them for what they are, we’ll only keep fighting in this never-ending, unproductive battle. Just like bratty toddlers.